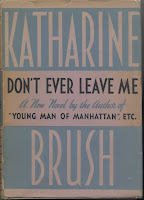

After Don't Ever Leave Me failed to wow the reading public, Kay found it difficult to do much writing. A novel begun during this period wouldn't be finished until some 7 years later (and would, quite sadly, end up being her last).

But between the years 1936 and 1941, Hollywood released at leat five motion pictures based on Kay’s work. Here’s a chronological rundown:

But between the years 1936 and 1941, Hollywood released at leat five motion pictures based on Kay’s work. Here’s a chronological rundown:

LADY OF SECRETS

Columbia, 1936

Columbia, 1936

Ruth Chatterton starred in this adaptation of Kay’s short story Maid of Honor, originally published in Cosmopolitan in September 1932, and reprinted several times.

The New York Times called Lady of Secrets “a picture that sashays back and forth in space and time without progresing far in any direction,” one that “is scarcely worthy of its cast…[which] moves stiffly and with obvious embarrassment through these morasses of plot and of dialogue…” Kay later defended her original story as “a pretty good one,” even if the resulting picture was an admittedly pretty bad one.

Lady of Secrets is the only picture of this bunch that I have not seen.

MANNEQUIN

MGM, 1937

Originally titled Marry for Money, the story was adapted as a vehicle for Joan Crawford, and paired her with leading man Spencer Tracy.

The New York Times said the picture

“restores Miss Crawford to the throne as queen of the woiking goils and reaffirms Katharine Brush’s faith in the capitalist system. That system…infallibly provides every poor but pure button-hole stitcher with an eventual millionaire who respects her and dangles a tempting wedding ring.

“So what we have, if you haven’t guessed already, is a sleek restatement of an old theme, graced by a superior cast and directed with general skill by Frank Borzage, who has a gift for sentiment. All that is more than the story deserves.”

Joan went on record saying that she wasn’t thrilled with Tracy, and it kind of shows in their on-screen chemistry. The two never appeared together again.

Joan went on record saying that she wasn’t thrilled with Tracy, and it kind of shows in their on-screen chemistry. The two never appeared together again.

MGM, 1938

Kay’s original screen story (not the screenplay) was developed from a minor background character that made a brief appearance in Don’t Ever Leave Me. The New York Times called it “winsome,” “a natural, pleasant and sensible little film. Judy Garland (who gets to sing three numbers, including “Zing Went the Strings of My Heart”) and Freddie Bartholomew kidnap their widowed mother (Mary Astor), lock her in a trailer and start touring the countryside in search of a suitable husband.

“If this sounds too cool-blooded and unromantic,” said The Times, “be reassured Freddie Bartholomew and Judy Garland conduct their matrimonial tour with charming unworldliness, despite the surface sophistication of their enterprise.”

It’s not giving anything away to say that the husband arrives, in the form of Walter Pidgeon.

Listen, Darling is certainly the best picture of this group.

HONEYMOON IN BALI

Paramount, 1939

Though Kay gets screen credit (along with Virginia Van Upp and Grace Sartwell Mason), virtually nothing of her 1936 story Free Woman was used, beyond the fact that the heroine is a successful and single career woman. Hardly an original idea.

And if, as The New York Times asserted, “the writers have reaffirmed the male prejudice so cogently and have given their own sex such short shrift,” if parts of the picture are “inexcusably tiresome,” one can hardly blame Kay; I've read the story and seen the picture, and I say that with absolute confidence. I actually find Honeymoon quite enjoyable.

Very interesting is that fact that, according to a 1936 announcement in The New York Times, Paramount intended to borrow Jean Arthur from her home studio Columbia to star her in an adaptation of Free Woman. That's the picture that should have been made!

And if, as The New York Times asserted, “the writers have reaffirmed the male prejudice so cogently and have given their own sex such short shrift,” if parts of the picture are “inexcusably tiresome,” one can hardly blame Kay; I've read the story and seen the picture, and I say that with absolute confidence. I actually find Honeymoon quite enjoyable.

Very interesting is that fact that, according to a 1936 announcement in The New York Times, Paramount intended to borrow Jean Arthur from her home studio Columbia to star her in an adaptation of Free Woman. That's the picture that should have been made!

ANDY HARDY'S PRIVATE SECRETARY

MGM, 1941

MGM, 1941

The New York Times didn't much care for this one, which is obvious from the opening line of Bosley Crowther's review:

“Thank heaven that Andy Hardy has finally graduated from high school and is on his way to college—the college of hard knocks, we hope.”

Rooney is really quite unbearable, full of snobbish condescension as the BMOC of Carvel High. He patronizes two poorer classmates (a brother and sister) by very generously allowing the brother to decorate the auditorium for the graduation exercises, and hiring the sister (Kathryn Grayson making her film debut) as his “Private Secretary.”

Because he’s spread himself so thin (because he’s such a vital force at Carvel), he flunks his English exams and nearly doesn’t graduate. But everyone rallies 'round their Andy, who, in the end, is rewarded with a shiny new roadster. “We hardly think Andy deserved it,” quipped Crowther. Of course, without access to Kay’s original story, there’s no way of knowing if the unpleasant changes noted in the Andy Hardy character can be attributed to the writing…

Kathryn Grayson, however, rated much higher in Crowther’s estimation:

“[She] makes [Andy] look like a chump by her grace and modesty.”

She sings in the picture, too. A little bit too much. I have to confess: I have never been a fan of Grayson’s. She’s always been a little too cute, a little too saccharin-sweet for my palette.

I absolutely HATE the ’51 remake of Showboat. Which is mostly her fault.

Sorry.

Sorry.