I just finished reading Red-Headed Woman. I had left it for later, as I mentioned previously, because I felt I already knew the story well enough from the movie.

In fact last night, with 20 or 30 pages left, I put the movie on, so that I could do a sort of side-by-side comparison. My initial assessment—that I knew it, the story—was only partially correct. The picture’s a good one, a lot of fun, but the book is, not surprisingly, much better, much fuller.

|

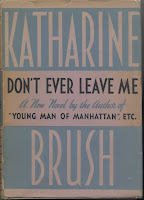

The jacket of the

movie tie-in edition |

The essentials are the same. Red-headed Lillian ("Lil") Andrews is from the "wrong side of the tracks." Lil works as a stenographer for the Legendres, who own a number of coal mines in Renwood, Ohio. Lil aspires to a more affluent, comfortable (well, pampered, really) life, and sets her sights on William ("Bill") Legendre, Jr. She uses her considerable feminine charms to seduce Bill away from his wife Irene. But even Renwood affluence isn’t enough for Lil, and, what’s worse, the social gates she thought would be flung wide to welcome her remain frustratingly, maddeningly barred. She decides it’s time to trade up, which she does by charming one C. G. Gaerste (rhymes with "thirsty"), whose wealth dwarfs that of the Legendres. ("You wouldn't call it money.")

Here’s where the stories diverge. In Kay’s original, Gaerste is, like Lil, an outsider of humble origins. Through hard work and sheer good luck he amassed his millions, which he now relishes in flaunting before all the world. Free of any “old money” snobbishness (to say nothing of restraint), he and Lil are simpatico. Gaerste sees Lil as simply another gorgeous, expensive ornament for him to dangle before envious, admiring eyes. Whether or not there’s any real affection between the two is completely beside the point.

In the movie, Gaerste is a bit of an old coot, a wealthy friend and business associate of the Legendres. At first resistant to Lil’s wiles, Gaerste must be won over with sex. And old coot or no, Gaerste is rich enough for Lillian to accept his proposal of marriage.

But then there’s a chauffeur (in the guise of Charles Boyer), a private investigator, a shooting, and an escape to Paris, none of which originated at the point of Kay’s pen. Oh well, both versions of the story end with Lil pretty much getting exactly what she wanted from the start.

Obviously, motion picture adaptations of literary works have to be condensed, streamlined. Characters get combined or added or eliminated altogether; events are truncated, shifted. At least this was the understood, the expected and accepted practice in 1932. Unfortunately, the central—it literally happens in the middle of the book—event in Kay’s original, the party scene, is shifted and condensed in such a manner and to such a degree that it loses most, if not all, of its impact.

The scene shows Kay at her best, I think, and can stand almost on its own as a story. It’s worth reading in its entirety, and if you’d like to do so, you can find it here.

Here’s the emotional climax:

She knew, she understood, then and thereafter. Her mind made swift and shattering translations. She could not delude herself, she could no longer, with the thin veil of Louise's subtlety, hide from herself Louise's meanings. Now she knew what all this was—deep in her mind she must have known it from the start, to know it so well now, to see it with such clarity. They were kidding her, these girls. Of course. Of course. They were giving her a ride. They were making fun of her, making a perfect fool of her—laughing at her behind the bright polite glaze of their eyes. They were collecting ludicrous quotations and descriptions, to take away with them; enough to last them for a long time. They were Irene's great friends, and this was sport and this was vengeance. So they had come. Now she knew well why they had come.

This was what happened, then. This was what you got. You were the red-headed Andrews girl from Renwood Falls, from the railroad crossing, and you stole a rich husband and bought a big house, and a Chinese Buddha, and a naked dress, and you tried to crash Society—and this was what you got. Never mind what you expected, hoped for. This was what you got. This was what Society did to you, to make you understand. You couldn't crash it in a million years.

The scene as Kay’s written it also highlights one of the less tangible differences between novel and movie. Watching Harlow give life to Lil Andrews, we are alternately amused and scandalized (assuming we’re an audience of 1932, anyway) by her wanton brazenness. But we never feel sorry for her. Not once. And while we might cringe at the behavior, the taste and the choices of Kay’s “heroine,” she’s not one-sided; something akin to pity is often aroused in the reader.

Pity for the outsider who so desperately wants to belong.

|

| photo of Kay from the first edition dust jacket |